“Water is best, and gold, like a blazing fire in the night, stands out supreme of all lordly wealth. But if, my heart, you wish to sing of contests, look no further for any star warmer than the sun, shining by day through the lonely sky, and let us not proclaim any contest greater than Olympia.” – Pindar, Olympian 1.

Last week we had a quick history lesson on the origins of the Ancient Olympic Games, recounting the myths of Pausanias and Pindar. This week we move on to the actual events of the Games and the roles of religion and politics in this ancient ritual.

Ancient Olympic Events

To participate in the Games, a free male Greek citizen had to qualify and have his name written in the lists. Once they arrived at Olympia, participants then took an oath in front of the statue of Zeus saying that they had been in training for 10 months. Married women could not participate in or even watch the Games, but unmarried women were permitted to attend.

Initially, the Games only lasted one day; in 684 BCE they were extended to three days and in the 5th century BCE they were extended further to five days (still relatively short compared to today’s Games that last close to three weeks).

The Foot Races

When the Games were only a day long, they consisted of one event: the stadion (“stade”) race. The stadion was a sprint, with athletes racing the length of the Olympia track (between 180 and 240 meters, or 590 and 790 feet).

The diaulos, a two-stade race, was added to the program in 724 BCE at the 14th Olympics. In this race, athletes ran one lap around the stadium (roughly 400 meters).

At the next Olympics in 720 BCE, the dolichos race was introduced. The exact length of the dolichos is unknown as historical accounts conflict with one another. The evidence we have of the race suggests that it likely ranged anywhere from 7 to 24 stades (about 5 km or 3 miles). Since this race was significantly longer than the stadion and the diaulos, the course extended beyond the stadium out into the Olympic grounds.

The hoplitodromos (“Hoplite race”) became an event much later in 520 BCE and was often the last race of the Games. This race greatly differed from the others in that the athletes ran a single or double diaulos…in full or partial armor…while also carrying a shield and wearing greaves (shin armor) and a helmet. This set of gear could weigh anywhere between 50 and 60 lbs, and the race was supposed to reflect the strength needed for warfare.

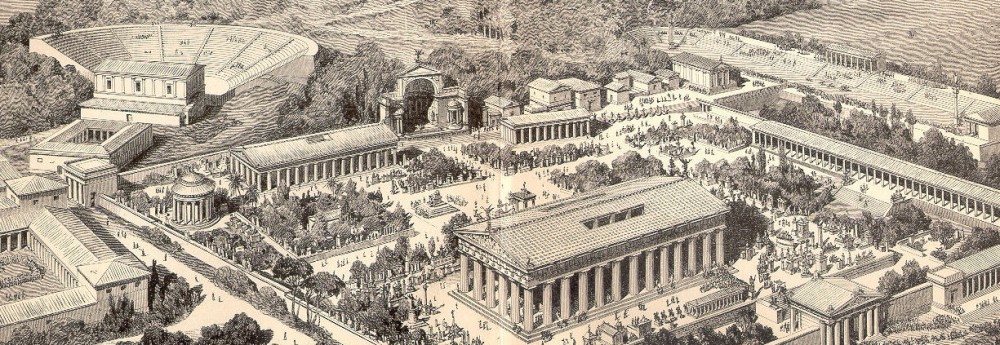

Aerial view of the stadium at Olympia:

Other Events

Boxing (pygme/pygmachia) and wrestling (pale) became events in 708 BCE, and pankration joined the bill in 648 BCE. Pankration was a crazy combination of boxing and wrestling that essentially had no rules; supposedly the only thing you couldn’t do was bite your opponent (sorry, Mike Tyson) or gouge out their eyes. Boxing became similarly intense throughout the years, with some athletes using hard leather straps to disfigure their opponents.

Pankratiasts fighting under the eyes of a trainer:

There was, of course, chariot racing (and other horse races) as well at the Ancient Olympics. Much like the horse racing we are familiar with today, the owner of the chariot and team was considered the competitor (not the rider) and could win multiple top spots.

And let’s not forget the pentathlon, the famed five-event Olympic sport. Added in 708 BCE with boxing and wrestling, the pentathlon consisted of wrestling, stadion, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw.

Famous Ancient Olympic Athletes

Astylos of Croton: won 6 victory olive wreaths in three Olympiads (488-480 BCE) in the stade and the diaulos.

Milon of Croton: six-time Olympic wrestling champion, seven-time Pythian Games champion, nine-time Nemean Games champion, and ten-time Isthmian Games champion.

Leonidas of Rhodes: won the stadion, diaulos race, and hoplitodromos in four consecutive Olympiads (164-152 BCE), won a total of 12 Olympic victory wreaths.

Melankomas of Caria: Olympic boxing champion in 49 BCE, known for his extremely agile fighting style.

Kyniska of Sparta: first woman to be listed as an Olympic victor, her four-horse chariot won in the 96th and 97th Olympiads (396 BCE and 392 BCE).

Religion

As I mentioned earlier, over time the Games grew to be five days long, two of which were for religious rituals. Since the Games were held in honor of Zeus, a sacrifice of 100 oxen was made to him during the Olympic festivities. Olympia became a central and common place for people to come to worship Zeus, and around 453 BCE the Greek sculptor Phidias erected a 42-foot tall statue of the lightning god in Olympia’s Temple of Zeus. This massive statue came to be considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

What the Statue of Zeus may have looked like in ancient times:

Politics

Since power in ancient Greece was centered around the city-state, and these city-states competed for resources while also having to rely on each other for trade and military alliances, the Olympics were a place where representatives from the city-states could peacefully compete against one another.

During the Peloponnesian War, alliances were announced at the Olympics and people at the Games also made sacrifices to the gods for victory in the conflict.

An Olympic truce, or ekecheiria, was observed during the Games. To announce the beginning of the truce, three runners went from Elis to all of the participating cities. When the truce was active, armies could not enter Olympia, wars were suspended, legal disputes were not allowed to go on, and the death penalty was forbidden. The truce allowed athletes and visitors to travel safely to the Games, and this tradition was renewed for the modern Olympics in 1998 (we’ll discuss this modern version of the truce at a later point).

Up Next

Now that we’ve given ancient times some attention and thought, I’ll be moving on to the modern Olympic Games and how a man named Pierre de Coubertin revived what was once an ancient ritual.